“Mindflight” In the Age of the Coronavirus – The “Blind Traveler” and His 250,000-Mile Epic Journey

With travel bans in effect worldwide, we can still set off on “mind travel” with the world’s epic explorers – like The Blind Traveler, called the “Greatest Traveler of All Time.”

The blind man picked up his walking stick, tapped its shiny metal tip on the ground, and began to walk.

He had only 250,000 miles to go, a mere quarter of a million miles, roughly the distance from earth to the moon.

It was 1819.

James Holman was no ordinary traveler. He was 32 years old when he set out, tapping his cane. Besides being blind, he had no travel guide, no accurate map of the world, no traveling companion, no tourist discounts, and no hotels along the way to turn in at nighttime when the sun set.

Over the course of the next four decades, Holman, a former British Navy lieutenant, would defy all odds and expectations and travel through Europe, Siberia, Africa, Brazil, India, Ceylon, China, Indonesia, and the Middle East. Along the way he returned home to England several times to recuperate before setting out again.

The “Blind Traveler,” as he came to be known in his meteoric rise to fame, did all of this by the transportation available at the time: carriage, cart, horseback, sledge, wind-driven water vessels, and briefly steam propelled boats. Along the way he also walked.

By the 1830s, he had achieved a kind of 19th-century rock star status, gaining the epithet “the greatest traveler in the history of the world” for sheer distance covered. (Marco Polo had traveled 15,000 miles. Ibn Battuta of north Africa traversed 75,000.) Holman maintained his record until the 20th century, when travel – and the world itself — were revolutionized by the coming of the distance-crunching combustible engine.

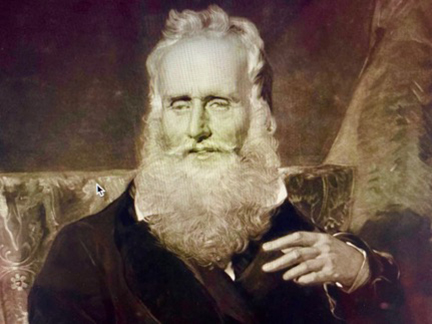

I met the Blind Traveler on a brief trek through a bookstore five years ago. I’d plucked a used book off the “Travel” shelf. It claimed to tell the story of how a blind man became history’s greatest traveler. This tested my credulity. I’d never heard of this explorer. I flipped through the yellowed pages of the heavily worn (and clearly loved) book. Towards the end, I encountered a man posing for a 19th-century portrait painting in a richly embroidered chair.

I stared at the man. He was clearly of an advanced age. He featured a glowing, almost otherworldly expression on his face, a gentle smile, a large intelligent forehead, and an overflowing white beard as eye-catching as God’s in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco. Holman’s eyes appeared vacant. But they were also strangely piercing, as if all the information stored behind them, collected by his other exquisitely honed four senses, still shone through to the front of his retinas by his very active brain.

Holmes stared beyond me. His gaze was low as if he were watching a setting sun, perhaps seeing again in his mind’s eye some distant landscape from one of the five continents he traveled between 1819 and 1852.

I would later discover that Holman served as a catalyst in the civil rights movement for disabled persons over a century later, a movement unheard of in his day. Holman embraced — even celebrated — his blindness. He daringly claimed that the blind were superior observers to the sighted. The blind enhanced their other four senses, ynchronizing them to gather richer data, while the sighted relied too heavily on sight, As a journalist later wrote of his extraordinary sensory powers, Holman “had eyes in his mouth, eyes in his nose, eyes in his ears, and eyes in his mind, never blinking.”

I paid $5 for the book. I took Holman home with me to get to know him better. I devoured the book in days.

I had once traveled alot myself with stints in Europe, Africa, and briefly the Middle East. As life changed and travel waned, my wanderlust never abated. It simply went inward. I found myself intensely reliving my own travels in living color. I could take off on “mindflight” in the middle of a film or book – accompanying Amelia Earhart flying her Electra over the Pacific or traveling with Nelly Bly when she did her own 8,000-mile circumnavigation of the world several decades after Holman, using many of its newly minted trains. These explorers’ journeys became my own journeys.

And this summer, when the pandemic got in full swing, I found myself turning again for inspiration and escape to the Blind Traveler as travel came to a grinding halt around the globe.

Holmes had not always been blind. He had joined the British Royal Navy at the tender age of 12 (enlisting as “13 years old” to get accepted). The British Naval was happy to take all the voluntary recruits they could find to defeat Napoleon on land and sea. The boy then served on dark and dank British battleships in the cold waters of the Atlantic for 12 years, becoming a lieutenant.

At 25, he began experiencing excruciating pain and swelling in his joints. Doctors diagnosed it vaguely as “a rheumatic condition.” Holman found it difficult to walk. He then lost his sight. He was given a modest pension and comfortable lodging at Windsor Castle, 25 miles due east of London, keeping company with a group of disabled and elderly men called the Naval Knights living quietly under the care of the Navy.

But Holman got sicker as his days passed there.

He remembered as a child that he wanted to “explore distant regions, to trace the variety exhibited by mankind under different influences of different climates, customs and laws.” After settling down in Windsor, he then proceeded to do just that. His doctors approved a short trip — having no idea of Holman’s true intent — hoping that clean air and warmer climes would improve Holman’s health.

On his first journey he traveled through Europe, Africa, and Brazil. In Sicily, he climbed to the top of Mt. Vesuvius as its spewed smoke and lava, and burned his walking stick. In West Africa, he contracted malaria and fought the slave trade, capturing three slave ships with 365 slaves. In South Africa, where he taught himself to ride a horse, he dodged Boer and English settlers and headed into Zulu territory. In Brazil, he ventured forth on a mule, nearly toppling over precipices in search of gold mines.

A second journey took him to Siberia. He traveled 3,000 miles overland across the Urals, hoping to reach the Pacific and travel through Asia. The tsar’s police stopped him at Urtusk, suspecting he was a spy. He was deported, ordered to recover his tracks on a sledge and nearly froze to death.

His third trip in 1827 took him around the globe. On the way, he hunted wild elephants in Ceylon, stopped in India and China, crossed Zanzibar and Tasmania by foot, and helped chart Australia’s outback. Returning to London five years later, he wrote his “A Voyage Round the World.”

When Holman set out again in 1840, aged 54, his final world destinations were Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Syria, the Holy Land, Bosnia, Montenegro and Hungary. Six years later, he returned to England and put up his walking shoes, the most traveled man of all time.

His influence extended even to Charles Darwin, a contemporary who confessed a debt to Holman. Holman had visited the island of Cocos where Darwin would go several years later in the Pacific. Holman’s description of the plants and topography were so detailed and accurate that Darwin cited them in his scientific writing.

Holman’s superstardom was dashed in his later years due to prejudice – a disbelief in his travels due to his blindness. But his life and work remained a monument to the world of travel, and a victory for the world of the disabled. In a long overdue recognition of his legacy, the international Holman Award was created in 2017 to support innovative projects by blind people around the world.

As the years passed, Holman recalled with “delight” his myriad travels, as if the recollecting of them were itself a form of travel — mindflight. His journeys even entered his dreams, as a journalist later wrote: “often, when first waking in the morning, he forgot in what part of the world he was.” When he passed in 1857 in his 70th year, his travels remained a testament to a fellow pilgrim of unique courage, achievement, and empathic goodwill for everyone he met.

Holman’s extraordinary life made me wonder about our own travel-restricted era. Like Holman, could we use our inner eye to see the world’s landscapes? Like Holman, could we transport our journeys into our dreams? Like Holman, could we feel gratitude for our own unique opportunities to explore the world?

On a brief walk today, an image of Holman’s face suddenly flashed across my mind. It came with an odd fleeting feeling, as if someone were walking beside me. For an instant I could almost feel Holman’s arm slipping gently through mine, a gesture he shared frequently with complete strangers while he traversed the world, to establish an immediate connection, to savor the new and unknown, to become friends.

In that instant, Holman and I traveled together in mindflight. As his cane tapped along, the whole world was briefly ours to share, to wander and wonder about. And then, as quickly as he arrived, he was gone again, on his way.

Thrive Global

7 October 2020