Rape of Nanking: Iris Chang’s Death Nine Years Ago Silenced A Voice Against Massacre

It was nine years ago that Iris Chang, the 36-year-old Chinese-American crusader for human rights, was found dead in her car off Highway 17 in an isolated spot near Los Gatos. She had shot herself in the head. She left behind many distraught admirers worldwide. She left behind many distraught admirers worldwide.

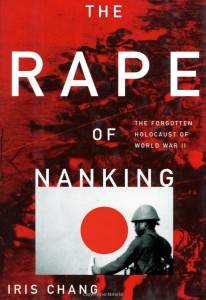

Chang’s meteoric rise to international fame came in 1997 with the publication of her history, “The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of the Second World War.” She charged that a mass murder of between 260,000 and 350,000 Chinese men, women and children had occurred over six weeks in one city in wartime China by invading Japanese troops in the winter of 1937 and 1938 — a crime so heinous she dared to use a word Jewish historians had reserved exclusively for the memory of their own dead in wartime Europe: holocaust.

Chang also claimed that between 20,000 and 80,000 women had been raped and then many of them killed in “one of the greatest mass rapes in world history.” “The Rape of Nanking” accused the Japanese government of a cover-up and demanded official acknowledgment and redress.

In an instant, Chang became a lightning rod for the intense feelings dividing nations about their respective histories. Chang’s supporters maintained that Japan needed to confront one of the most grisly episodes of its wartime past. Her critics maintained that Chang either grossly distorted what happened or made up the story altogether.

In what is perhaps the most widely quoted excerpt from her introduction, Chang writes, “The Rape of Nanking should be remembered not only for the number of people slaughtered but for the cruel manner in which many met their deaths. Chinese men were used for bayonet practice and in decapitation contests. An estimated 20,000-80,000 women were raped. Many soldiers went beyond rape to disembowel women, slice off their breasts, and nail them alive to walls.

“Fathers were forced to rape their daughters, and sons their mothers, as other family members watched. Not only did live burials, castration, the carving of organs, and the roasting of people become routine, but more diabolical tortures were practices, such as hanging people by their tongues on iron hooks and burying people to their waists and watching them get torn apart by German shepherds.

“So sickening was the spectacle that even the Nazis in the city were horrified, one proclaiming the massacre to be the work of ‘bestial machinery.’ ”

To counter charges that she was “Japan bashing,” Chang acknowledged that long-standing imperialistic ambitions of other world powers — including China and Europe — led up to the conflict. She was interested in how “the power of cultural forces” either “make[s] devils of us” or keeps our humanity intact.

We are compelled by Chang’s death to direct our focus toward the almost incomprehensible numbers of individuals who died by mass murder globally — 170 million, by some estimates — in the 20th century alone.

When Chang took her life on an isolated road nine years ago, the voiceless lost a singular voice.

…rape-nanking-iris-changs-death-nine-years-ago

On Tuesday, November 9, 2004, Iris Chang, the 36-year-old Chinese American crusader for human rights, was found dead in her car off Route 17 in an isolated spot near Los Gatos, California. A single bullet was lodged in her head. She left behind a 2-year-old son, a husband and many distraught admirers worldwide.

Iris Chang’s meteoric rise to international fame came in 1997 with the publication of her history The Rape of Nanking; The Forgotten Holocaust of the Second World War. The book sent shock waves through the international community. Chang charged that a mass murder of between 260,000 and 350,000 Chinese men, women and children had occurred over six weeks in one city in wartime China in the winter of 1937 and 1938 – a murder so hideous that she dared to use a word Jewish historians reserved for the memory of their own dead in wartime Europe: holocaust. In addition, Chang claimed, between 20,000 and 30,000 women had been raped, many of them killed, in “one of the greatest mass rapes in world history.” Using previously untapped historical documents in four languages and extensive interviews with Chinese survivors, Japanese soldiers, and foreign witnesses, The Rape of Nanking accused the Japanese government of a cover-up and demanded official acknowledgment and redress. Critics in Japan, including a number of academicians, quickly responded by condemning Chang’s deceit and “trickery.”

In an instant Chang became a lightning rod for the intense feelings dividing nations and governments about their respective histories. Lionized as a messenger of truth to some, deemed as a hate-monger by others, Chang set off a chain reaction of passionate support and animosity that leapfrogged over several continents. Chang’s supporters maintained that Japan needed to confront the most grisly episode of their wartime past. Her critics maintained that Chang either grossly distorted what happened, or made up the story altogether.

Chang’s death has been called a suicide. Chang reportedly suffered a breakdown during a trip to the Philippines where she had begun work on a book about the Bataan Death March, the April 1942 forced march of 70,000 Allied POWs by Japanese soldiers leading to the deaths of up to 10,000 troops by exhaustion, beatings and execution. After hospitalization in the Philippines and her return home, Chang’s husband Brett Douglas described her as a “changed person.” In light of this, it was apparently decided – by Douglas alone or by the two of them together – that their infant son should be shipped off to live with Douglas’ father in Illinois. On the morning of her death Chang left a suicide note asking her family to remember her as being “engaged with life, committed to her causes, her writing and her family,” according to Chang’s former editor. The note is reported to have been painstakingly written, edited and rewritten.

Two days following Chang’s death, when national and international headlines ran the news following the police investigation, my teenage son walked into my office and glanced at my bookcase, which included Chang’s book. He remarked offhandedly, “She killed herself.” “Who?” I asked, puzzled, not yet knowing the news. “The woman who wrote The Rape of Nanking.” “Iris Chang?” “Yeah, I just read it in the newspaper.”

The spasm of grief I felt at that moment I am certain was felt by thousands of Chang’s readers in this country and around the world. Whether by suicide or homicide, the loss of this scholar and human rights advocate took on all the dimensions of the tragedies she had spent years writing about.

What had happened? Had history’s demons – its brutality, tyranny, and unconscionable loss of innocent life – weighed too heavily on her mind? Did she believe her efforts were in vain? Was the stigmatization she received from Japanese critics too much to bear? Could personal factors have played a part, as she faced raising an infant son after pursuing a high profile international career?

Chang once said in an interview about The Rape of Nanking that it was a book “I really had to write. I wrote it out of a sense of rage.”

Did Chang die of rage, a rage that consumed her physical and mental health?

A conspiracy theory also surfaced that Chang had been assassinated by Japanese secret agents. Following the news of her death I read comments devoted on a website with the heading, “Why Did Irish Chang Kill Herself?” The unnamed site manager initially balked at emailers claiming Chang was murdered. “There is a lingering suspicion of foul play,” he or she wrote. “Where is the proof? I am debating whether to delete these posts claiming without proof or even persuasive argument that Irish Chang was killed by some person or persons unknown… OR, I could start a branched topic on this particular ‘conspiracy’ aspect of Iris Chang’s death.”

The site manager chose to open discussion about a possible conspiracy.

“Iris Chang was murdered by the Japs in a revenge slaying designed to silence and discredit her,” commented one emailer. “The killing had to be masterminded by Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia.”

“I am calling the investigation police not to close its book on Iris Chang’s death,” wrote another. “Perhaps the local police should give this case to the FBI to examine any validity on the conspiracy theory since there are many Japanese interests would like to see Iris dead. The FBI can then find out why Iris carried a handgun. Were she and/or her family threatening? [sic]… The public deserve [sic] to know the truth surrounding Iris’ death.”

“Many people have expressed their doubts upon learning of the suicide of a young, beautiful and intelligent writer Iris Chang,” still another charged. “[Chang]… was not on a mission to demonize Japan in WWII but rather to seek the truth and justice for hundreds of millions of Asians suffered, tortured and killed in the hands of ruthless Japanese soldiers… Japan is now eager to expand their business in China and other Asian countries. There are good reasons to believe that Japan and/or its surrogates do not want Irish to publish another book detailing the cruelty and inhumane behaviors perpetrated by Japanese in the past.”

The fact that Chang’s death has given rise to this heated debate is evidence of the extraordinary controversy that has surrounded Chang’s effort to expose a hidden “holocaust” since the book’s publication in 1997. It is a controversy that ultimately touches upon Chang’s integrity as a messenger of history and a public advocate for justice. It focuses the debate about genocide “deniers,” and exposes the anger and insecurity people and nations still feel about their respective histories and character.

In what is perhaps the most widely quoted excerpt from her introduction, Change writes, “The Rape of Nanking should be remembered not only for the number of people slaughtered but for the cruel manner in which many met their deaths. Chinese men were used for bayonet practice and in decapitation contests. An estimated 20,000-80,000 women were raped. Many soldiers went beyond rape to disembowel women, slice off their breasts, and nail them alive to walls. Fathers were forced to rape their daughters, and sons their mothers, as other family members watched. Not only did live burials, castration, the carving of organs, and the roasting of people become routine, but more diabolical tortures were practices, such as hanging people by their tongues on iron hooks and burying people to their waists and watching them get torn apart by German shepherds. So sickening was the spectacle that even the Nazis in the city were horrified, one proclaiming the massacre to be the work of “bestial machinery.”

Chang cites figures from experts at the International Military Tribunal of the Far East about the numbers killed: “more than 260,000 noncombatants died at the hands of Japanese soldiers at Nanking in late 1937 and early 1938, though some experts have placed the figure at well over 350,000.”

Chang’s revelations released an international uproar. By coincidence, a similar explosion of feeling had occurred one year before with the publication of Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s book Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Goldhagen appeared to take the whole nation of Germany to task, charging that the “vast majority” of Germans were “eliminationist” anti-Semites who became potential “exterminationists” under National Socialism. Like Goldhagen, some felt Chang also crossed an unacceptable boundary line in her unforgiving portrait of the Japanese.

One does not have to go far to see how ferocious the opposition to Chang’s account of events in Nanking became.

A website entitled “Iris Chang’s Errors In ‘The Rape of Nanking’ – looking for truths in the sea of war-time propaganda” is a case in point. The unnamed sponsors of the site claim they “cannot ignore the book’s inability and refusal, as witnessed by the usage of numerous doctored photos, to differentiate between fact and war-time fiction. We dedicate this site to all those who believe that constructive relations between nations and peoples should stem from an honest look at historical truths, not propaganda or twisting of historical materials for what appear to be political gains.” The site, “updated 04/01/2000,” claims to contain “direct quotes, translations, or abridged versions of scholarly works by Japanese historians or researchers.”

What follows is an odd collection of fragmentary statements by Chang followed by equally fragmentary rebuttals. The “doctored photos” screen shows only two photos whose captions are questioned. There is in addition the full text of a talk given by Asia University Professor Higashinakano Shudo to the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan on September 30,1999. “The Rape of Nanking cannot be called a history book,” Shudo states. “…[T]here are about 170 simple mistakes on historical facts, but even those mistakes seem irrelevant compared to the groundless descriptions of cruelty supposedly committed by the Japanese. [Chang’s]…descriptions of cruelty are beyond the imagination of the ordinary Japanese. However, such cruelties, including cannibalism, appear frequently throughout China’s history, even as recently as the Cultural Revolution.”

By this account, perpetuators of barbarities of war could only have been Chinese, not Japanese.

Chang’s scholarship may indeed have debatable numbers or assertions in it. But it goes without saying that historical writing almost inevitably contains gray areas because there is almost no “perfect” historical record from which to draw interpretation. Those who wish to deny Chang’s effort altogether would appear to belong in that fascinating but disturbing category of “deniers” of history, acting as individuals or groups so (whatever their nationality) when it is difficult to confront the ugliness of their own past, even hiding it from themselves. Germans still sympathetic to the National Socialist vision of German “purity” have been busy trying to do this for 50 years regarding the “accuracy” of the accounts of their own genocide historians.

In any study of Chang’s life and work, one must ask if her critics had any grounds to stand on. To do this properly means separating reasonable critical scrutiny about her work from polemical outrage about Chang’s alleged “trickery.” Chang was charged with “manipulation” in conservative Japanese publications; she also drew criticism from several U.S. scholars on Japan.

Andrew Horvat, Tokyo representative of the San Francisco-based Asia Foundation, has said that “there will always be controversy over the accuracy and balance of her writings,” but that she “did raise a level of consciousness that wasn’t there before. In that sense I think her contribution was very positive.”

Indignant over Chang’s treatment by certain Japanese academicians, an email supporter of Chang commented after her death: “I would like to let all know that there is a book ‘Nanking Massacred – Japan’s rebuttal to China’s forged claims’ by professor Tadao. The English translation and the original Japaness [sic] version were combined into a book, which was published by a book company [sic] in Japan. I would like Iris’s book to be translated into Japaness [sic] as a forceful rebuttal to the rebuttal. It is too bad that University of Tsukuba has such an ‘INTELLECTUAL’ like Tadao.”

If Chang’s book has not been published in Japan it is remarkable that a book refuting Chang’s claims has. This might be comparable –though the analogy is not perfect – to publishing Carl Olson’s The Da Vinci Hoax while not publishing Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, a widely popular novel with widely disputed historical claims.

Chang herself reflected that “[w]hat baffled and saddened me during the writing of this book was the persistent Japanese refusal to come to terms with its own past… Strongly motivating me throughout this long and difficult labor was the stubborn refusal of many prominent Japanese politicians, academics, and industrial leaders to admit, despite overwhelming evidence, that the Nanking massacred had even happened… In Japan, to express one’s true opinions about the Sino-Japanese War… continues to be… career-threatening, and even life-threatening. (In 1990 a gunman shot Motoshima Hitoshi, the mayor of Nagasaki, in the chest for saying that Emperor Hirohito bore some responsibility for World War II.) This pervasive sense of danger has discouraged many serious scholars from visiting Japanese archives to conduct their research on the subject; indeed, I was told in Nanking that the People’s Republic of China rarely permits its scholars to journey to Japan for fear of jeopardizing their physical safety.”

To counter charges that she was “Japan bashing,” Chang gave her overarching view on the global theater of war and the longstanding territorial ambitions of other world powers that led up to that conflict.

“In recent years sincere attempts to have Japan face up to the consequences of its actions have been labeled ‘Japan bashing.’ It is important to establish that I will not be arguing that Japan was the sole imperalist power in the world, or even in Asia, during the first third of this century. China itself tried to extend its influence over its neighbors and even entered into an agreement with Japan to delineate areas of influence on the Korean peninsula, much as the European powers divided up the commercial rights to China in the last century.”

“Even more important,” Chang added, “it does a disservice not only to the men, women, and children whose lives were taken at Nanking but to the Japanese people as well to say that any criticism of Japanese behavior… is a criticism of the Japanese as people. This book is not intended as a commentary on the Japanese character or on the genetic makeup of a people who commit such acts. It is about the power of cultural forces either to make devils of us, to strip away the thin veneer of social restraint that makes humans humane, or to reinforce it. Germany is today a better place because Jews have not allowed that country to forget what it did nearly sixty years ago. The American South is a better place for its acknowledgement of the evil of slavery and the one hundred years of Jim Crowism that followed emancipation. Japanese culture will not move forward until it too admits not only to the world but to itself how improper were its actions of just a half century ago. Indeed, I was surprised and pleased by the number of overseas Japanese who attend conferences on the Rape of Nanking. As one suggested, ‘We want to know as much as you do.’”

Whatever else may be said, the country and the international community have lost a young scholar and advocate who rose above both the cut-and-dry AP reporting world and detached academia to tackle a subject so taboo and horrifying that it may have contributed to her premature death. The late American historian Stephen Ambrose called Chang “maybe the best young historian we’ve got, because she understands that to communicate history, you’ve go to tell the story in an interesting way.” The personal issues to explore in Chang’s life are there: a childhood filled with stories about Nanking told by two quietly “outraged” parents, both refugees from China who became professors of physics and microbiology at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana; Chang’s realization as a young adult after China’s 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre that she shared an oral tradition about an unrecognized “holocaust” with others of Chinese descent; and Chang’s unquestionable brilliance – her original training in science writing, her fluency in Mandarin, her craftsmanship as a writer.

And then there are the many aspects of Chang’s public life: her appeal to a wide reading public hungry for suppressed history, the intense campaign to get her work acknowledged by the Japanese government and the subsequent counter-campaign, Chang’s public advocacy of historical accountability by governments, her defense of race- and color-free standards in society, and the inspiring model she provided many young Chinese-Americans. Chang had gained the international spotlight initially in 1995 with the publication of Thread of the Silkworm, a book exploring the life of Chinese rocket scientist Tsien Hsue-shen who was deported from the United States during the McCarthy era and then headed up the Chinese missile defense program. Following The Rape of Nanking Chang turned her talents to investigating the immigrant history of her ancestors in The Chinese in America, a book receiving wide acclaim.

Underneath all of this we return to the question of who Chang was in the years and days preceding her death.

How had she evolved emotionally over the course of her harrowing investigative work? Had those around her really supported her psychologically, in addition to lending their professional or intellectual support? Despite her disclaimers, could she possibly have harbored any hidden animus towards the Japanese people or culture that colored her approach to her subject? Could she possibly have even questioned the integrity of her own writing and had undisclosed misgivings?

Did she know when to stop, to rest or redirect her energy?

Did she fear reprisal – or death – from her critics and enemies?

Could family life with a new baby have competed with her sense of obligation as an international speaker and advocate of human rights and bringing genocide to light? Could she laugh when she was not in the role of historical detective and voice of conscience? What was her faith, if any, or philosophy of life? Was history her God, and did history let her down? What markers might we find along the way that revealed the increasingly dark state of her interior life? And was there a specific place in her internal journey where she lost her way?

How did Japanese government officials, academics and diplomats treat Chang, either in writing or in person? Who were her hardest critics and why? Did she receive any death threats, or threats to her physical safety that she ever acknowledged?

After the gun went off in Chang’s white 1999 Oldsmobile sedan on November 9th and the investigators had filed their reports, “stunned friends and colleagues sought to understand what might have led to the suicide,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle.

Chronicle book editor Oscar Villalon noted Chang’s achievement as “one of the most visible Chinese American authors, who wrote a landmark book that brought the attention, at least among her American audience, what was nonexistent as an issue.”

“This is a huge loss,” said Helen Zia, author of Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People. Chang “wanted to bring voices to the fore, the stories shunted aside and ignored in history.”

“It’s shocking to lose such a young and talented person,” commented Ling-Chi Wang, professor of Asian American studies at the University of California at Berkeley. “She was passionate and articulate.”

Over the course of her short life, Chang received numerous honorary degrees and lectured widely at universities and conferences here and abroad. She earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Illinois and then worked briefly as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune and AP. After entering a master’s writing program in 1990 at Johns Hopkins University she took a vocational turn that would change her life. Thus began her freelance career investigating the “voices of the voiceless.” Her intense dark eyes and youthful face became familiar to television viewers who saw her on “nightline” and Jim Lehrer’s “NewsHour.” She also appeared on the cover of Reader’s Digest and wrote for numerous publications, including the New York Times and Newsweek.

On the day of her death, Chang’s husband filed a missing person’s report with the police at 5:30 a.m. He had risen early to find his wife gone.

For Chang’s followers, the shock of her death is all the more painful because it makes one thing irrevocably clear: what should have been a long creative output over several decades by this energetic woman came to a crashing halt on November 9th. Chang’s exceptional gift for breathing new life into history, her public determination to see this done, and her abiding concern for human rights, are gone.

One mourner expressed the wish that others would pick up where Chang left off. “I hope someone will… continue [Chang’s] work on the Bataan Death March,” the mourner wrote. “My great uncle, Captain George Bernard Moore, was in the Bataan Death March. He was an officer in Company I, 45th Infantry Regiment, Philippine Scouts… I ask that Iris Chang’s work be continued in her honor and that she should be given credit as well if a book is made. It is only fitting that her sacrifice be not in vain.”

Writing in an unusually intimate vein in her introduction to The Rape of Nanking, Chang recalls the overwhelming feeling that she felt at a conference in December 1994 devoted to the victims of the Nanking atrocity. Held in Cupertino, California, and sponsored by the Global Alliance for Preserving the History of World War II in Asia, the conference provided an instant of self-realization for Chang.

Her words hold a mysterious sway in light of what has come to pass.

Looking at photos from wartime Nanking for the first time, Chang recalls, “In a single blinding moment I recognized the fragility of not just life but the human experience itself.” “We all learn about death while young. We know that any one of us could be struck by the proverbial truck or bus and be deprived of life in an instant. And unless we have some religious beliefs, we see such a death as a senseless and unfair deprivation of life.”

Chang continued: “But we also know of the respect for life and the dying process that most humans share. If a bus strikes you, someone may steal your purse or wallet while you lie injured, but many more will come to your aid, trying to save your precious life. One person will call 911, and another will race down the street to alert a police officer on his or her beat. Someone else will take off his coat, fold it, and placed it under your head, so that if these are indeed your last moments of life you will die in the small but real comfort of knowing that someone cared about you.”

In that moment came catharsis.

“The pictures up on the walls in Cupertino illustrated that not just one person but hundreds of thousands could have their lives extinguished, die at the whim of others, and the next day their deaths would be meaningless. But even more telling was that those who had brought about these deaths (the most terror-filled, even if inevitable, tragedy of the human experience) could also degrade the victims and force them to expire in maximum pain and humiliation. I was suddenly in a panic that this terrifying disrespect for death and dying, this reversion to human social evolution, would be reduced to a footnote of history, treated like a harmless glitch in a computer program that might or might not again cause a problem, unless someone forced the world to remember it.”

Out of this Chang’s mission was born, her irrepressible desire to provide a “small but real comfort” to the dead by telling their story, however incomplete that record might be.

We are compelled by Chang’s death to look at the fragility of life ourselves, and the components of mind and will and matter that make it up. We properly direct our compassion for the almost incomprehensible numbers of individuals who have died by genocide worldwide – roughly 170 million in the 20th century, by some accounts. But there are also other less conspicuous victims: those witnesses who have by word or deed fought this demon of history and attempted to bring it to the attention of the world.

It is striking that in the weeks preceding Chang’s death the New York Review of Books ran a profile by Samantha Power of the Canadian U.N. peacekeeping commander Major General Romeo Dallaire, who attempted to stop the 1994 100-day killing spree in Rwanda of an estimated 800,000 Tutsi by the nation’s rival ethnic group the Hutu. Power’s piece echoed her findings in the 2002 book A Problem From Hell; America In the Age of Genocide about the emotional risks entailed in Dallaire’s heroism.

“The genocide in Rwanda cost Romeo Dallaire a great deal,” wrote Power in A Problem From Hell. “It is both paradoxical and natural that the man who probably did the most to save Rwandans felt the worst. By August 1994 Dallaire had a death wish. ‘At the end of my command, I drove around in my vehicle with no escort practically looking for ambushes,’ Dallaire recalls, ‘I was trying to get myself destroyed and looking to get released from the guilt… I cannot erase the thousands and thousands of eyes that I see, looking at me, bewildered.’”

Change may have felt the same desire to ambush herself, brought on by the pressures of her vocation and the circumstances of her life. Like Dallaire, she was in “a vehicle with no escort” when the ambush occurred. We can all certainly wish in retrospect that Chang could have found the solace for herself that she offered to others. Even if there exists the remotest possibility that others were involved in this tragic loss of life, investigators should explore all leads.

In the meantime, the voiceless have lost a singular voice.

Mercury News

14 December 2013