A Profile In Resilience — The Story of Nien Cheng and Her Life After Solitary Confinement and Torture

How can we grow in resilience? In her prison cell, Nien Cheng cultivated inner resources which offer us lessons when we feel alone and abandoned.

We all have felt alone and abandoned at times.

We all have felt that heightened state of fear and dread as we faced some state of imminent danger. We may have lost the trail on the mountain that we had climbed. We may have received a prognosis we did not expect and no one to share it with. We may have discovered we had the wrong map on the highway in the pitch black of night. We may have taken the wrong turn navigating a foreign city. We may have been fired from our jobs for no reason. We may have fled a country where we were tortured. We may have been watched by our neighbors and threatened by our government. We may have been beaten by a mob. We may have lost our entire family in a crisis.

Loneliness is a part of life. Abandonment stalks some of us more than others. Our greatest fears and trauma are part of history’s personal and collective record. And so is our capacity to seek ways out of the turmoil, to rebuild our lives, to reorient ourselves — even transforming our perception of who we are and of reality itself — to grow beyond the entrapments of profound trauma.

Great leaders have always showed us how to do this. Sometimes we discover these heroes within our own families. They transmute their experience of isolation by filling it with a tenacious impulse to grow within it — to fill its empty spaces with as much intention as possible until the danger has passed, until the trail is retrieved, until the wounds are healed, until the light shines again down the terrifying dark path.

Their stories are steeped in the history and culture of their time. But they belong to no single nation, to no single generation. As much as we would like to claim them as exceptionally “our own,” their stories remain indelibly personal while undeniably archetypal. They belong in the archive of the ages, of the human family — offering lessons for us all.

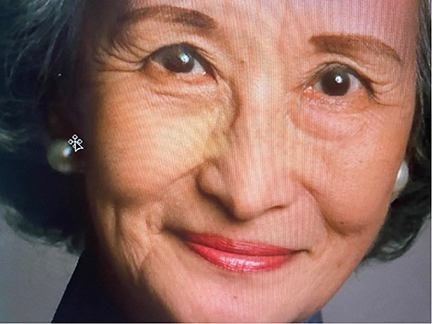

One of the most resilient individuals I ever met was a 115-pound woman from Shanghai who stood well below my shoulders and had multiple scars on her wrists and body from torture. Years before during China’s Cultural Revolution she had been thrown in prison after being charged as “an enemy of the state”. Nien Cheng remained in solitary confinement for six and a half years from 1967 to 1973. She was then released in good standing with no proof of any crime.

She would later leave China and immigrate to America. When I discovered she lived in Washington D.C., just forty-five minutes away from where I lived, I tracked down her phone number. I called and asked if she would be interested in an international speaking engagement about her six-year detention at the height of the Cultural Revolution. She was then in her eighties. It had been more than thirty years since her imprisonment.

The voice I heard at the other end was bird-like and brisk. She spoke with unusual urgency. “I am retiring soon,” she said. I braced for her decline. But her energy seemed high. She paused for a second. “Well, I would like to make this my final public address.”

We agreed. I would pick her up the following week. As she climbed into the car I discovered myself sitting next to a slight woman dressed in a neat black jacket with square shoulders. Her gently curled soft grey hair framed her small fragile-looking head. She had a beautiful smile. Her cheeks were rosy. Her eyes were penetrating. She spoke a crisp and flawless English with a pronounced Chinese accent.

At a glance I would never have thought my car companion had survived over six years of grueling mock trials, beatings and interrogations by guards, meals of moldy food scraps, and a freezing prison cell. She sat erect in the front seat of a Honda van. Dwarfed by the car’s dimensions, she filled the space with an intense alertness and energy.

By this time I had read Cheng’s extraordinary autobiography Life and Death In Shanghai. It had been a bestseller and sold over a million copies in several countries. We began to discuss it as we drove.

One summer morning in 1966, Cheng heard a ferocious banging at her door. Thirty-five to forty Red Guard youth had collected in front of her house, crashed through its door, and began breaking furniture, smashing glass, and looting.

This scene at Nien Cheng’s house in the city of Shanghai was repeating itself in other cities across China and elsewhere in the countryside. It was the culmination of seventeen years of communist rule under Chairman Mao Zedong, who came to power in 1949.

In his early days as China’s new leader, after years of fighting warlords and a corrupt nationalist government, Mao planned to transform China into a modern industrialized state. He hoped to do this while achieving a second goal: to lift up its vast peasant class, who lived in abject poverty — like animals,” some have written — under modern-day feudalism. Cheng and her husband had sympathized with Mao’s vision. Both hoped for significant reform to create greater equality in China. As members of the educated class, they trusted Mao to bring this about.

Mao proceeded at a devastating breakneck speed to collectivize millions of peasants into state-run enterprises. He used mass murder along the way to eliminate any opponents to his plan. Millions of peasants gained health care and education for the first time in history. But millions more — including peasants unwilling to collectivize their farms — were killed for asking any questions, for any resistance. Mao’s mandate for re-envisioning society quickly transformed into a rule of terror.

By the mid-1960s, Mao was worried. Moderates in the Communist Party wanted to reverse policy failures, loosen up the tight grip of power, slow down the speed of change, and allow greater freedom in China. They were unenthusiastic about Mao’s utopian visions. They were critical of the death toll these visions entailed.

Mao objected. He called upon Chinese youth — called Red Guards — to eliminate all vestiges of traditional Chinese society and market-style economic activity. A new and volatile vanguard, they were to seek out and humiliate, torture, or destroy business owners, teachers at all school levels, the university-educated, the elderly burdened with “old ideas,” citizens in cultural pursuits like theater and the arts, and anyone with foreign connections.

All these now became “enemies of the state” — criminals to be punished.

Cheng knew all this when the Red Guards crashed through her door that summer morning in 1966. Once they began their rampage inside, they locked her in her dining room. They ripped down curtains, slashed paintings on the wall, and took cameras and clocks. They burned Cheng’s books on a bonfire outside.

“You are a class enemy!” the Red Guards shouted after they unlocked Cheng from her dining room and encircled her. She was knocked over and kicked and sent upstairs as the Red Guards settled in.

Cheng’s counterrevolutionary crimes were clear. She had come from a well-to-do family, had lived and worked overseas, and she had associated with foreigners. Cheng was accused of being a “foreign spy.” Her husband had once been employed at the foreign affairs ministry. The two moved to Australia to help set up a Chinese embassy. Their daughter was born there. They chose to return to China when Mao assumed power because they had idealistic hopes for the future and wanted to see more equity in society and democratic reform in their homeland. Cheng’s husband was appointed by Mao’s government to serve as its representative to Shell Oil Company in China, which provided the country with pesticides and fertilizers. Cheng herself became a company advisor when her husband suddenly died. She later retired.

But by 1966, in the radicalized atmosphere of the Cultural Revolution, Cheng’s prior position with Shell raised suspicions. The enraged Red Guards who encircled her in her home expected her to confess to being a spy. She did not.

She was placed under house arrest. She was then taken to an empty building in the city and underwent the first of countless “struggle meetings” against her in which the accused “criminal” was interrogated and grilled by anonymous jurors and then mocked and beaten by an assembled crowd to force a confession from the accused. Cheng again insisted on her innocence. She was manacled and taken to Shanghai’s infamous Number 1 Detention Center, the high-security prison for political “enemies of the state.”

She was led down a dark decrepit hallway with a long line of dark decrepit doors closed with padlocks. She now became Prisoner #1806. One door was opened. She was forced inside. The padlock snapped shut.

For the next six and a half years, from 1967 to 1973, Cheng stayed in solitary confinement. Her tiny cell had a filthy bed and exposed concrete toilet. The walls were so cracked she glued toilet paper to them with rice residue to prevent dirt from falling on her mattress. She spoke to guards through a small opening with a shutter in the cell door. She received her daily bowl of watery rice and boiled cabbage there.

The guards shouted at her to walk around her cell at a set hour for exercise. The guards shouted at her to pick up her step as she walked in the small prison yard and exercised by herself. A naked bulb lit over her bed shined down on her through the night. Her movements were watched through a peephole in the door around the clock. She sewed her threadbare clothes with strips from a towel in her cell. She washed herself from a water bowl.

She was beaten, tortured, and interrogated repeatedly. She was sick frequently. At times heavy metal manacles were placed on her bleeding wrists.

Through all of this she still maintained her innocence. She mentally resolved never to confess to a crime she had not committed. She would also never see her daughter Meiping, a 24-year-old successful actress in Shanghai, again.

Cheng was finally released in 1973. The political winds of change had come to China. They were not favorable to Mao. More moderate communist leaders had regained power. They called for less repression, reversing government failures, and establishing a more open economy. Mao died three years later. As soon as Cheng was freed she was told her daughter had died by suicide. She doubted this. She later discovered Meiping had been tortured and killed.

How did Nien Cheng endure this unimaginable torture and loneliness?

As Cheng and I took the highway exit ramp out of Washington D.C. on the way to her speaking engagement, we began to talk about this. She elaborated on one of the central themes of her gripping page-turner autobiography: resilience. Much of what she shared during our drive resonated immediately with me — I had found her account in Life and Death In Shanghai riveting. I was astonished that I was now driving down the highway with the protagonist of that story sitting next to me.

She told me one key to her survival was maintaining human contact — however fragmentary that might be in solitary confinement. She spoke openly about the depression and despair that came at times and what she did to fight them off.

“Whenever deep depression overwhelmed me to the extent that I could no longer sleep or swallow food,” she recalled in her memoir, “I would intentionally seek an encounter with the guards.” Even when a fight ensued, she felt her “calm spirits” restored with this renewed human contact.

Astonishingly she even felt empathy for her abusers at times. Cheng understood that prison guards were ordered to be brutal to their prisoners — or risk being brutalized themselves. Despite this, on occasion, a few even slipped items to her secretly through the shuttered opening in the door. She knew the risk they took. She knew they lived in their own state of terror.

She maintained human contact in other ways. One morning when Cheng’s watery rice bowl was pushed through the small shuttered opening in her cell door she noticed that the face on the other side looked different. Cheng detected a smile. It was a large and warm smile — a forbidden act. It was the face of the new young woman prisoner assigned to bring her food. The two were forbidden to speak to each other. The two were forbidden to smile at each other. The two could both be severely punished for either infraction. Still, every day, the prisoner who brought Cheng her bowl dared to smile. Cheng dared to smile back. Cheng looked forward to their secret forbidden smiles.

Human contact in the prison hospital also restored Cheng when she was sick with tuberculosis and hemorrhaging. Cheng felt her humanity restored under the care of the doctor who was also a prisoner at №1 Detention Center. She recalled the doctor’s “deeply lined face with graying hair at her temples“ and the kindness of her eyes. She “spoke softly, as if she saw something good and lovable in me. There was something saintly about this woman… She had obviously become a finer person because of her suffering.”

Cheng looked for all traces of nature in prison to keep her spirit alive as well. She was ecstatic one day to discover a spider joining her in her cell as it crawled through the rusted metal grate on the cell window. Spellbound, Cheng watched as the tiny creature began to weave its web and settle down in its new home. Thrilled by its company, awed by its movements, Cheng watched it build and rebuild its web in the broken places day after day. She was inspired by her companion’s determination.

The spider produced a web that was “intricately beautiful and absolutely perfect,” she observed. Its immaculate design reflected an “architectural feat of an extremely skilled artist, and my mind was full of questions… How big was the brain of such a tiny creature? Did it act simply by instinct, or had it somehow learned to store the knowledge of web making?” At sunset she watched the web dazzle with rainbow colors as the setting sun refracted off its surface. Prisoner and spider became steadfast friends. “A miracle of life had been shown to me,” she recalled. “My spirits lightened.”

Cheng also spotted nature during her forced exercise hour. In the prison yard with its cracked plaster walls Cheng saw “resilient weeds struggling to keep alive.” With their perfectly shaped pink flowers, they “stood proudly in the sunshine giving a sign of life in this dead place. Gazing at the tiny flowers, which seemed incredibly beautiful to me, I felt an uplifting of my soul.”

Cheng took time — sometimes hours — also gazing up at the narrow strip of sky through the iron bars of her cell window. The opening there with its daily light gave her reason to live, to fight on. In a kind of meditative state, she seemed able to disconnect from her physical body entirely. The opening in the window was the “only channel through which I maintained a tenuous connection with the world outside,” she said. “Often, while my body sat in the cell, my spirit would escape through the window to freedom.”

She also made a habit of listening to the prison guards in their conversations outside her cell. This also helped her gain information about the outside world. She noted when they spoke of political changes that bode well for her possible return to freedom. She extracted information from her interrogators as well, when they inadvertently divulged political news during interrogations. And she skillfully read “between the lines” in the Chinese communist party newspaper placed in her cell to find out more news and stay in touch with the world.

She also found ways to reconnect with herself.

Every morning just before the dawn, when the guards switched off the light that shone incessantly through the night over Cheng’s bed, Cheng discovered she was finally alone, unwatched, unmonitored. Her cell was still and quiet. Her mind was free and clear. “I recovered the dignity of my being and felt a sense of renewal.” She became herself again.

She also connected with the transcendent. In her quiet moments of daily prayer she discovered she could push away her fears and regain her equilibrium. She disguised what she was doing by leaning her head over Mao’s Little Red Book, whose quotations she had already memorized. At times her prayers deepened and took on a new nature. “In the drab surroundings of the gray cell, I had known magic moments of transcendence that I had not experienced in the ease and comfort of my normal life… My belief in the ultimate triumph of truth and goodness had been restored, and I had renewed courage to fight on.”

When she became depressed thinking about Meiping, she disciplined her mind to turn from thoughts of her death to thoughts of her living. “More and more I remembered the days of her living, and less and less I dwelled on the tragedy of her dying. Gradually peace came to me and with it a measure of acceptance.”

Cheng also remained unwavering about her innocence, even if that meant death. She adroitly defied her interrogators by mastering quotations by Mao himself from the Little Red Book. When her interrogators asked why she continued not to confess, she always answered that she had committed no crime and could therefore logically make no confession.

“I will obey our Great Leader Chairman Mao’s teaching. ‘Firstly, do not fear hardship, and secondly, do not fear death.’” she answered. She challenged her interrogators to “shoot me if you prove I have committed a crime.” She wrote down for their records, “Prove that I did something wrong and I will accept the death sentence.”

She remained at her core “an eternal optimist,” hoping a rigorous examination carried out by the authorities would ensure that justice would be done and she would be freed.

Despite sleepless nights and endless beatings, Cheng kept envisioning a future outside prison — a future she would spend with her daughter. When she learned that Meiping had died, she recommitted herself to finding out how Meiping had died, to seek justice for it, and to preserve her daughter’s memory. “It was up to me to find out what had happened… and to right the wrong that had been done to her.”

In 1973, Cheng was released from prison. She weighed 85 pounds. She lost 30 pounds. She was no longer Prisoner #1806. She regained her name. At age 58, she was finally “rehabilitated” by the government. She was provided a home on the second floor of a home in Shanghai where she lived until she emigrated.

For the first time in over six years she looked into a mirror and was horrified by what she saw reflected back. Even this experience she transformed through a philosophical lens.

“I was shocked to see a colorless face with sunken cheeks, framed by dry strands of gray hair, and eyes that were overbright from the need to be constantly on the alert. It was a face very different from the one I once had. But after all, six and a half years was a long time. I would have aged in any case. I looked at myself again. I hoped that in time my cheeks would become rounded and my eyes would look at the world with calm appraisal rather than anxious apprehension.”

As she said she would do, Cheng finally learned the facts of Meiping’s death. She had been detained and interrogated after Cheng was imprisoned. When Meiping refused to condemn her mother, she was tortured and killed. Now that Cheng was free, she arranged for a commemoration in Meiping’s honor. Meiping’s murderer was charged and sentenced to death. The sentence was later commuted. But by shining the light of truth on her daughter’s fate, Cheng finally had closure. She made peace with her death.

It was time to leave China. In 1980 Cheng was granted a passport. She traveled to Taiwan and then Canada. She moved to Washington D.C. in 1983.

Turning off the highway, Cheng and I arrived in good time for her speaking engagement. I gave a brief introduction before a wide-eyed audience. Copies of Life and Death in Shanghai were stacked for purchase. In the question session that followed, some asked about China’s politics and history. Others asked about how Cheng survived in solitary confinement. She discussed her tenacious grip on reality, her personal struggles, and her hope in political change. She discussed her daughter Meiping for whom she resolved to stay alive.

Cheng’s story, like all great stories of heroic resilience, continues to fascinate us, as it will future generations. She considered herself an unflagging patriot of her country. She evinced compassion for people of all walks of life.

If history had been different, this tiny tenacious woman from China might have lived under less extreme circumstances and watched as her country corrected its past inequities by other means. Instead she took lessons from the persecution that impacted her life directly. She remained a passionate internationalist, engaged with the wider world to expand her understanding of other people and cultures, while never forgetting the people and culture from which she came.

Whatever the limitations of her perspective, we cannot deny her penetrating voice and searing observations on the value of life. We cannot forget the astonishing manner in which she found the means to overcome its hazards and cruelty.

In her new home in Washington, she confessed that often in the darkness of morning she woke with a certain sadness. But as the day progressed, her gratitude returned. Each day, she realized, provided “new opportunity.” In the twenty-six years before her death at the age of 94 in 2009, Cheng continued to tap into the same life-restoring reserves that transmuted her post-traumatic stress into post-traumatic transformation.

When I drove Cheng back to Washington after her last public address, she invited me to return for a tea. We met again and talked for two hours. Towards the end of our visit she spoke suddenly about death. I was caught off guard.

“I am very old now,” she said.

I nodded and waited for her to continue. Despite her being in her eighties, there was still a visible spark in her.

“But I am not afraid of dying.”

I awkwardly filled in the pause.

“Well, you seem very alive and well to me,” I said, smiling.

“I am doing reasonably well,” she said. Then she hesitated. “But I am having some health issues.”

“I’m so sorry to hear that. Please let me know if there is anything I can do.”

“No, all is well.”

She suddenly looked me directly in the eyes. She had something else to say. I waited.

“All is well. I will finally see my daughter Meiping again.”

It was a cathartic moment. Her face seemed to relax. In the more than thirty years since her daughter had been murdered, Cheng had found a new home, traveled internationally, written her page-turner memoir, held speaking engagements, supported Chinese students studying in America, and made a new life in a new land.

She had done what masters of resilience do when they transform trauma into triumph — she had purposefully filled the greatest void in her life with meaningful action. Now her steadfastness would pay off.

We emptied our teacups. Cheng showed me a photo of Meiping. Then she flashed a mysterious smile at me. I saw a glint of joy in her eye.

We said goodbye.

As the door closed, I knew I had met a unique witness to life. I knew I would never see her again.

Some time later, a friend called. “Did you see the news, that Nien Cheng has died?” she asked. I located Cheng’s obituary in the newspaper.

As I read it, I remembered our tea together. I remembered the instant she entrusted me with her most private unspoken joy. I remembered the glint in her eye. And I remembered her mysterious smile.

For Cheng the path was filling with light again. She was moving on.

Medium

2 March 2021